This article demonstrates the power of modern C++ in financial analysis context. It is aimed at those already familiar with C++ as it does not define basic programming concepts, however it will demonstrate the use of some new C++20/23 features. If you are a intermediate C++ programmer looking how to apply skills to a real world problem, this should be a great article for you.

Who needs ranges?

The new ranges library is amazing for many different reasons; the two most important being safety and maintainability. Using ranges improves safety by removing the possibility of out-of-bound errors and improves maintainability by creating a simple to follow syntax that is composable. Other benefits of ranges compared to traditional looping techniques include the lack of allocations, laziness of ranges, and re usability.

Example Problem

Rather than explain the power of ranges with some generic learning example, I wanted to demonstrate the usefulness with something people could actually use. I decided on time series analysis; more specifically calculating the alpha and beta between a stock and an index. If you are unfamiliar with what alpha and beta are, read the next paragraph. If you are already familiar, feel free to skip to the next header.

Alpha and Beta?

Alpha and beta are two measures commonly used in stock analysis.

The beta of a stock to an index is the slope of the best fit line between the returns of the target stock and the index. The beta of a stock can be seen as a proxy for the undiversifiable risk associated with the company. If the target stock has a beta of 1.5, it will be expected to produce returns 1.5x that of the index stock. For example, a 1% increase in the index stock will lead to an expected 1.5% gain in the target stock that has a 1.5 beta.

Alpha on the other hand is the y-intercept of the best fit line. Alpha represents the return that was earned in excess of what beta predicted over the period. As mentioned previously, beta is a proxy for risk, so earning in excess of what beta predicts is creating superior risk adjusted returns. Therefore, a higher alpha represents a higher return per unit of risk; investors always want a higher alpha.

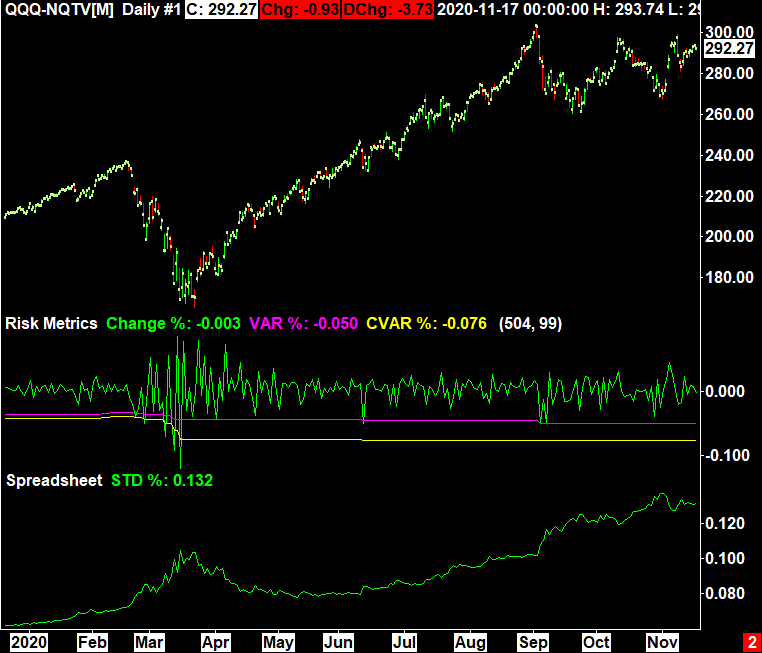

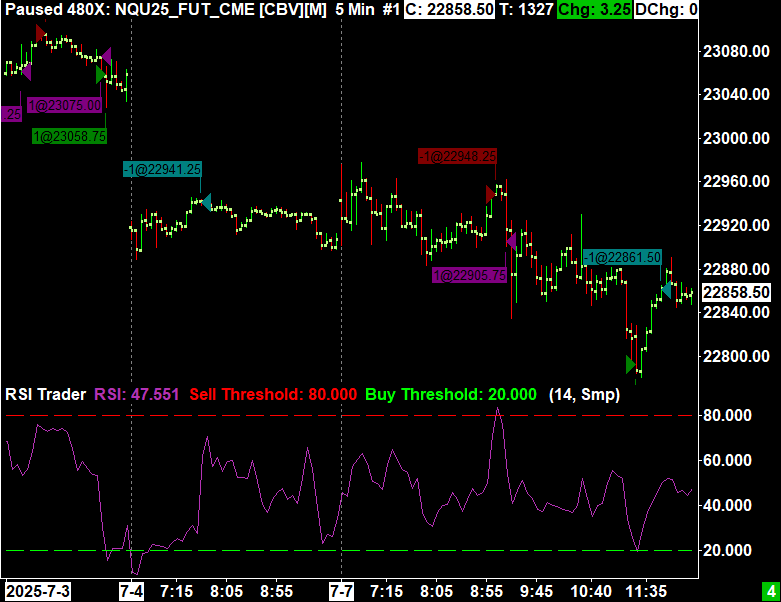

Sourcing the data

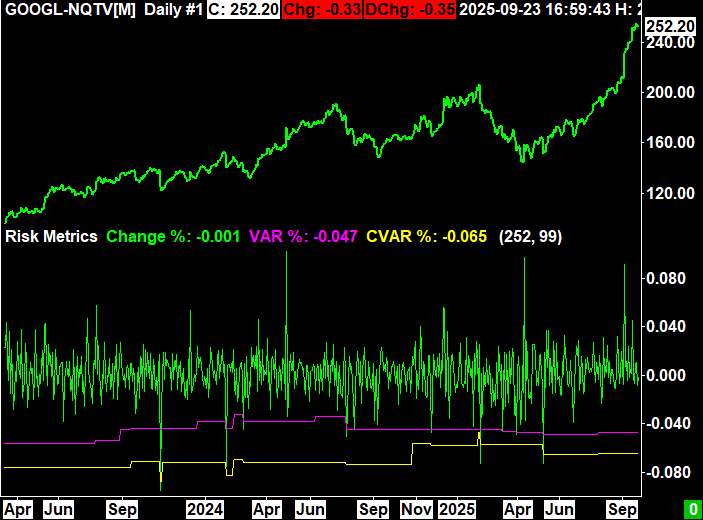

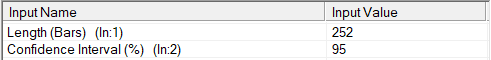

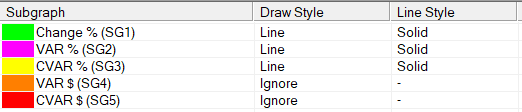

In order to operate on a dataset, we need to actually get a dataset. My solution to this is using SierraChart to export data in a CSV format. The benefit of using a CSV as an intermediate layer is that anyone reading should be able to substitute the correct format of values from a different data source. The format of SierraChart’s CSV is shown to the right.

Date, Time, Open, High, Low, Last, Volume, OpenInterest

2025/1/8, 00:00:00, 588.70, 590.58, 585.20, 589.49, 47304672, 0

2025/1/10, 00:00:00, 585.88, 585.96, 578.55, 580.49, 73105048, 0Parsing the Data

Following good C++ practice, we need to create a class to represent the bar data to be parsed from the CSV file; we will name that class CBarData. The CBarData constructor will take a line from the CSV of data and parse it into the respective open, high, low, and close member variables.

class CBarData {

public:

double m_Open{ 0.0 };

double m_High{ 0.0 };

double m_Low{ 0.0 };

double m_Close{ 0.0 };

public:

CBarData(const std::string& Line);

};Next, a class is required to represent a time series, we will call this class CTimeSeries. The class will consist of a vector of CBarData representing the underlying bar data. This class can be easily extended to hold different derivations of the base price; in this example we will derive the change from the previous bar’s close. The CTimeSeries class will also now hold a vector of doubles which represent the change from the previous bar close. The CTimeSeries constructor can now handle the calculations of changes easily.

class CTimeSeries {

public:

std::vector<CBarData> m_BarDataList{};

std::vector<double> m_PercentChanges{};

public:

CTimeSeries(const std::filesystem::path& Path);

};At this point we now have our raw price data CSV parsed into a valid and complete CTimeSeries.

Using Ranges

Now that we have two CTimeSeries we are able to start the beta and alpha calculation process. This is where the new ranges library makes huge changes. We will compose a view over the vector of changes contained in the CTimeSeries. Due to the change calculation being based on the previous bar close, there is no change for the first bar. Ignoring the first x number of elements is exactly what std::views::drop(x) does! Next, we need to select x number of the most recent days, and we can use a combination of std::views::reverse() | std::views::take(x).

const auto TransformPipeline = std::views::drop(1) | std::views::reverse | std::views::take(NumBars);We can refer to this series of 3 steps as a transformation pipeline which can be reused on multiple sets of data. After applying this transformation to the price change vector, we have a properly sanitized view of percent changes over the selected range of changes. We will then pass these ranges of data to the final class; CLinearRegression.

Beta Calculations

We create a CLinearRegression class which takes two ranges as inputs for each the x and y ranges of percent changes. Upon construction it will calculate the slope and intercept of the ranges and store the result into member variables. The calculation of beta and alpha also are made much easier with ranges. The use of std::views::zip, std::views::transform, and std::ranges::fold_left make the calculation process intuitive to follow.

class CLinearRegression {

public:

template<std::ranges::viewable_range rng>

CLinearRegression(rng X, rng Y) {

if (X.size() != Y.size() || X.size() < 2) {

throw std::invalid_argument("Ranges must be of the same size and contain at least two elements.");

}

auto XSquared = std::views::transform(X, [](double x) { return x * x; });

auto XYProduct = std::views::zip(X, Y) | std::views::transform([](const auto& pair) { return std::get<0>(pair) * std::get<1>(pair); });

auto XSum = std::ranges::fold_left(X, 0.0, std::plus<double>());

auto YSum = std::ranges::fold_left(Y, 0.0, std::plus<double>());

auto XSquaredSum = std::ranges::fold_left(XSquared, 0.0, std::plus<double>());

auto XYProductSum = std::ranges::fold_left(XYProduct, 0.0, std::plus<double>());

m_Intercept = (YSum * XSquaredSum - XSum * XYProductSum) / (X.size() * XSquaredSum - (XSum * XSum));

m_Slope = (X.size() * XYProductSum - XSum * YSum) / (X.size() * XSquaredSum - (XSum * XSum));

}

const double& GetSlope() const { return m_Slope; }

const double& GetIntercept() const { return m_Intercept; }

private:

double m_Slope{ 0.0 };

double m_Intercept{ 0.0 };

};Final Code

Putting it all together we create a simple program that takes 3 inputs from the user to run the regression and output the result. The complete code can be found on the following GitHub repository.

#include "pch.h"

#include "Classes/CTimeSeries.hpp"

#include "Classes/CLinearRegression.hpp"

int main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

if (argc < 4) {

std::println("Usage: <TargetTicker> <IndexTicker> <NumBars>");

return 0;

}

std::string TargetTicker = argv[1];

CTimeSeries TargetTimeSeries(std::format("C:\\SierraChart\\Data\\{}-NQTV.dly_BarData.txt", TargetTicker));

std::string IndexTicker = argv[2];

CTimeSeries IndexTimeSeries(std::format("C:\\SierraChart\\Data\\{}-NQTV.dly_BarData.txt", IndexTicker));

size_t NumBars{ std::stoul(argv[3]) };

const auto TransformPipeline = std::views::drop(1) | std::views::reverse | std::views::take(NumBars);

try {

CLinearRegression Regression(IndexTimeSeries.m_PercentChanges | TransformPipeline, TargetTimeSeries.m_PercentChanges | TransformPipeline);

std::println("[{0:s}-{1:s}] y={2:.2f}x{3:+.4f}", TargetTicker, IndexTicker, Regression.GetSlope(), Regression.GetIntercept());

}

catch (const std::invalid_argument& e) {

std::println("Error: {}", e.what());

}

return 0;

}Example Usage/Output

>reg QQQ SPY 250

[QQQ-SPY] y=1.17x+0.0000

>reg GOOGL QQQ 250

[GOOGL-QQQ] y=0.91x+0.0015

>reg META QQQ 250

[META-QQQ] y=1.18x-0.0005

>reg GOOGL META 250

[GOOGL-META] y=0.37x+0.0021